When it comes to food safety in Nepal, two realities are pretty well established: The fruits and vegetables we consume, be they imported or homegrown, contain high pesticide residues; and the government, desperate to fulfil the ever-increasing demand, has hardly the willpower or the infrastructure to conduct tests to ensure that the fresh produce we consume is free of contaminants. To be fair to the government, it did make efforts, through a Cabinet decision in June last year, to quarantine and conduct pesticide residue tests for agriculture produce imported from India. But the decision was ill-thought-out and its implementation chaotic. The government soon revoked its decision, thanks partly to its own inefficacy and partly to pressure from the Embassy of India in Kathmandu. That was the last we heard from the government about its plans to ensure that the food we eat is edible.

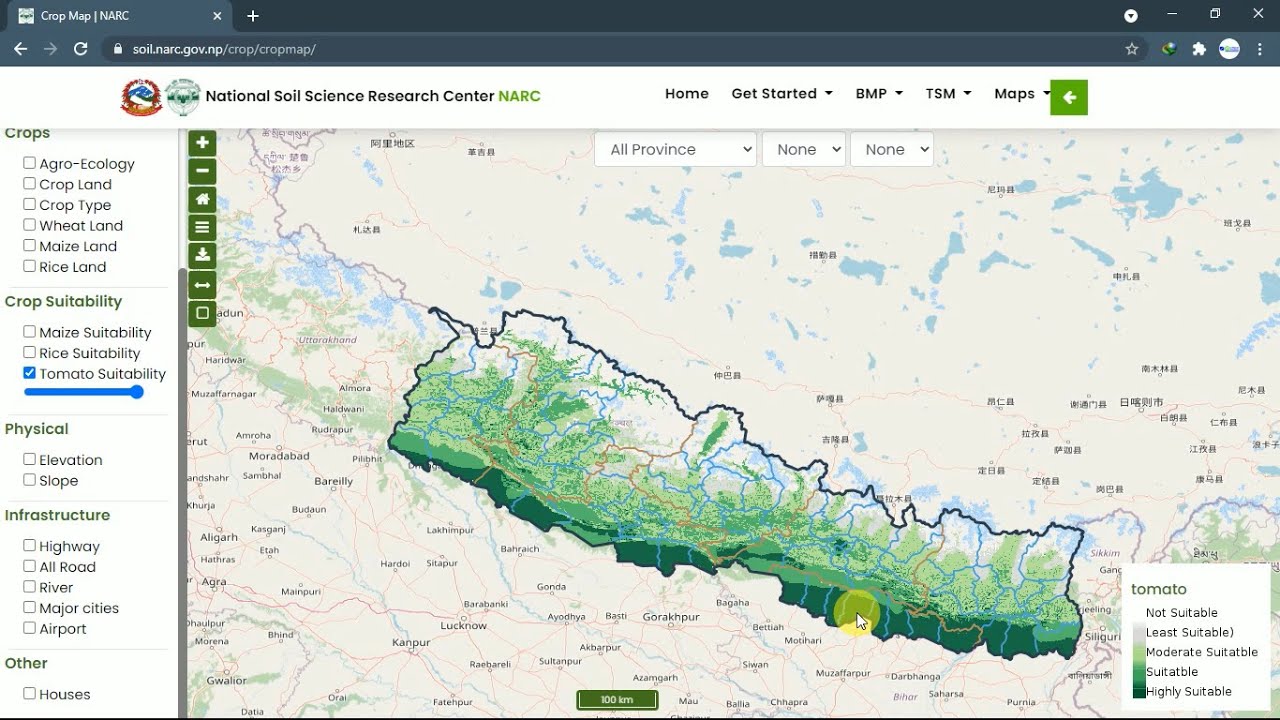

A 2019 research paper titled ‘Pesticide residues in Nepalese vegetables and potential health risks‘, published in the journal Environmental Research assessed pesticide residues in vegetables and the related health risks to humans, and found a high hazard index for organophosphates, the pesticide Nepal considers as a health hazard. The study, which assessed 27 eggplant, 27 chilli and 32 tomato samples, found out that 93 percent of the eggplant samples and all of the chilli and tomato samples had pesticide residues. Moreover, multiple residues were observed in 56 percent of the eggplant samples, 96 percent of the chilli samples and all of the tomato samples. The research showed that 4 percent of the eggplant samples, 44 percent of the tomato samples and 19 percent of the chilli samples had multiple pesticide residues including triazophos, omethoate, chlorpyrifos and carbendazim that exceeded the European Union’s maximum residue limits.

However, Nepal faces a severe lack of well-equipped laboratories to test for such residues. What’s more, the laboratories that are in operation conduct a limited range of tests. This means that the vegetable and fruit imports come directly to our kitchens without the required tests. Officials at the Central Agricultural Laboratory concede that there is a severe lack of infrastructure to conduct pesticide residue tests at the border points. They say the pesticide residue testing labs need upgradation for them to be able to test for a wider range of residues in imported fruits and vegetables. As of now, the Rapid Bioassay for Pesticide Residue (RBPR) units located at several border points test only for carbamate and organophosphate pesticides. This means that they are unable to test for other types of hazardous pesticides that could have been used to avoid the tests.

What’s more, the limited tests show results that even the government officials find incredible. Of the 12,557 samples tested by the Sarlahi unit of the RBPR, all showed an enzyme inhibition percentage of below 35 percent. Of the 103 samples tested by the Kaski unit, 98 were found to be edible; and of the 6,208 samples tested by the Kailali unit, 6,198 were found to be edible. This gives rise to two questions: Are the labs at the border points ill-equipped to test the residues or are the shipments entering the country without any tests? Whatever the answer, it is bad news for Nepali consumers: There’s poison on our plates.

But the government continues to find itself in a double bind: If it does not import vegetables and fruits from India, there will be a severe shortage leading to a jump in the price of these consumables. But when it does, it has neither the infrastructure to test for a wide range of pesticide residues that pose a severe health hazard for the citizens nor the willpower to go against the big lobby that ensures that Nepal imports the consumables without tests. The government has no option but to urgently update the laboratories at the border points and widen its range of tests to ensure that the consumables that enter the kitchens of the Nepalis are free of hazardous pesticide residues. -kathmandupost